DISEASE AREA

Acquired haemophilia

Acquired haemophilia (AH) background

- AH is a disease of elderly. Only few cases are reported during pregnancy/postpartum.

- AH is a rare, autoimmune bleeding disorder characterised by bleeds that are often severe and can be life-threatening.1-3

- The most common type, acquired haemophilia A (AHA), is caused when the body creates inhibitors against factor VIII (FVIII) which interfere with blood coagulation (by blocking Factor VIII).4

- AH occurs in patients with no previous history of bleeding1,3 For every million people, there are approximately 1.5 cases of AH each year.2

AH requires prompt recognition and appropriate management

- AH treatment involves haemostatic treatment to stop the bleed and immunosuppressive treatment to eliminate the inhibitors.1

- Although some patients do not present with extensive bleeding, all patients are at risk of fatal bleeds, irrespective of bleeding severity at presentation, so urgent diagnosis and haemostatic treatment is required in most cases.1-3

- The rarity of AH means that patients often present initially to physicians who have not had previous personal experience with the disease.1

- Low awareness of AH may contribute to diagnostic delays, with diagnosis taking more than a week for onethird of patients.5

- Delays in diagnosis can have serious consequences for patients as it can lead to more severe bleeding.2-5

- It is very important to avoid invasive procedures in patients who may have AH since even minor procedures and venepuncture can lead to uncontrollable bleeding.1

- Patients with a suspected rare bleeding disorder, such as AH, should be referred to an expert haematologist as soon as possible.1-2

Abnormal bleeding

- AH is usually diagnosed after investigation of abnormal bleeding, although some patients present with an abnormal routine coagulation test, rather than bleeding.1

Isolated prolonged aPTT

- The single most important clue to an AH diagnosis is an isolated prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), which is present in all patients with AH.2-5

Never leave a prolonged aPTT unexplained

- This may be the only clue if a patient is not bleeding at presentation and should never be left unexplained.1

Typical patient profile

- AH is usually seen in older people, both male and female, with a median age of 64-78 years.1,5

- AH can also be associated with pregnancy.1,5

- AH is not associated with family or personal history of bleeding disorders.1,5

Typical clinical indicators of AH

- AH should be considered in patients, especially elderly and

peripartum women with:

- Acute or recent onset of abnormal bleeding1

- Isolated prolongation in activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)1

- Normal prothrombin time (PT)1

- Acute or recent onset of abnormal bleeding1

- Most patients with AH have extensive subcutaneous bleeds.1,2,5

- Other soft tissue and mucosal bleeding is also common.1,2,5

- Bleeding into

joints is uncommon1,2,5

- 5-10% of patients have no bleeding at diagnosis1,2,5,6

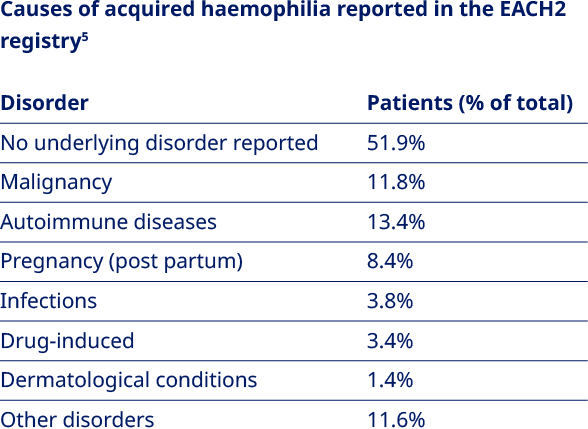

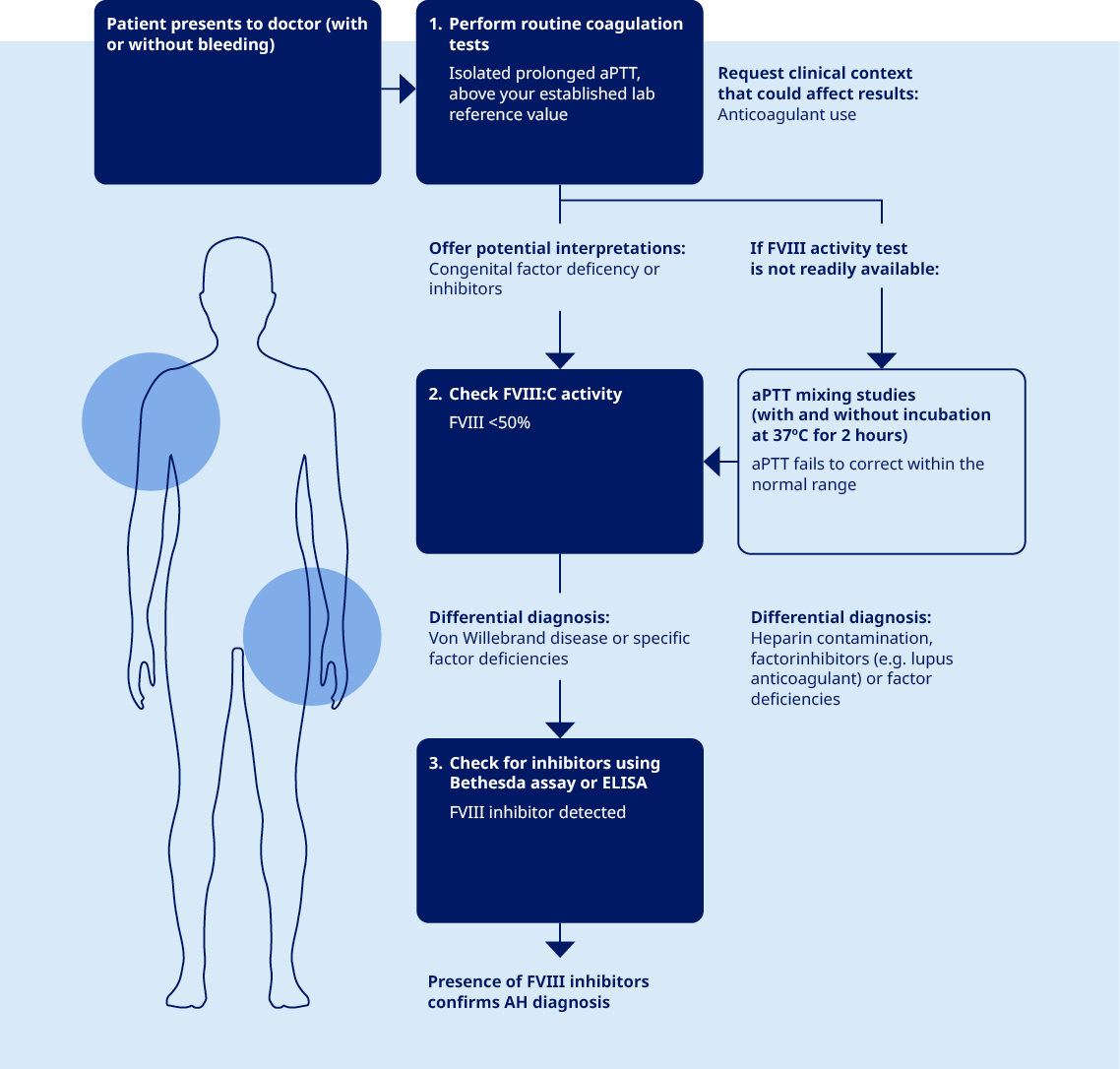

Three diagnostic tests confirm a diagnosis of AH:1,6,7

- It is relatively straightforward to diagnose AH using the

appropriate laboratory tests.1

- aPTT

- FVIII activity

- Bethesda assay/ELISA for inhibitor detection

- Consultation with a haematologist or haemophilia treatment centre may support accurate diagnosis and necessary treatment.1,2

Accurate and timely laboratory results are essential when diagnosing AH1,2,6,7

- A missed aPTT prolongation could result in lifethreatening bleeding if the patient is sent for surgery.

- Clear communication can ensure that the laboratory is aware of the urgency of the results and the physician is alerted to any values outside of the laboratory reference range.

Immediate actions if you have a patient with AH

- Avoid invasive procedures.1,2

- Even minor procedures can lead to uncontrollable bleeds.2

- Control bleeds with a haemostatic agent.*1

- Consult a haemophilia treatment centre.2

* The decision to initiate haemostatic treatment is guided by the clinical relevance of acute bleeds1

Your expert interpretation is vital

- AH can easily be missed as it is very rare and usually occurs in elderly patients with co-morbidities and no history of abnormal bleeding.2 In approximately 5-10%of cases, the patient is not bleeding at diagnosis and abnormal coagulation test results are the only clue.1,2,5,6

- All patients with AH have a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) - a crucial clue that is often overlooked.2,5

- Flagging when an aPTT result is outside of your laboratory reference range can help the physician to reach a diagnosis of AH more quickly.1-2

- Even minor procedures and venepuncture can lead to uncontrollable bleeding in patients with AH, so a quick diagnosis is important to avoid inappropriate management that may lead to more severe bleeding.1,2,8

- Doctors need support from radiologists to interpret CAT scans - laboratory results are no different. Communicate your interpretations to help diagnose AH quicker so the bleeding can be stopped and secondary bleeds avoided.2

Three diagnostic tests confirm a diagnosis of AH:1,6,7

- It is relatively straightforward to diagnose AH using the

appropriate laboratory tests.6,7 Three diagnostic tests

confirm a diagnosis of AH1,6,7 – guide doctors on what

the results mean.

- aPTT

- FVIII activity

- Bethesda assay/ELISA for inhibitor detection.

Accurate and timely laboratory results are essential when diagnosing AH1,2,6,7

- A missed aPTT prolongation could result in lifethreatening bleeding if the patient is sent for surgery.

- Clear communication can ensure that the laboratory is aware of the urgency of the results and the physician is alerted to any values outside of the laboratory reference range.

Your expertise can help doctors help patients

- Flag when results are outside of your laboratory reference range.2,8

- Help doctors to understand the results so they can diagnose AH quickly.2,8

- Advise doctors on which tests are needed to confirm or rule out AH before any invasive procedures are performed.2,8

Tiede A et al. Haematologica; 2020;105:1791-1801.

Collins P, et al. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:161.

Baudo F, et al. Blood. 2012;120(1):39-46.

Baudo F, De Cataldo F. Haematologica 2004;89:96-100.

Knöbl P, et al.J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(4):622-631.

Tiede A, et al. Sem in Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(7):803-811.

Tiede A, et al. Hamostaseologie. 2015;35(4):311- 318.

Collins PW. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9 (Suppl. 1 ):226-235.